RACE: Recognizing, Assessing, Controlling, & Evaluating Hazards

Not all of us work in roles that are considered dangerous. But just because you don’t have a “dangerous job” doesn’t mean that you or your employees can’t suffer a workplace accident. Every single job has its own hazards. If you don’t take those hazards seriously, every job becomes a dangerous job. Recognizing, assessing, controlling, and evaluating hazards is integral to the safe operation of an organization.

If you have served on a Joint Health and Safety Committee (JHSC) you should already be familiar with the steps in identifying and understanding workplace hazards. We call this process “recognizing, assessing, controlling, & evaluating” or “RACE” for short. It’s a process designed to identify and address workplace hazards.

This article covers in detail the four parts of RACE. It’s a great resource for you to share with newer members of your JHSC or managers and supervisors tasked with hazard or risk assessment.

Recognizing Hazards

Before you can address the dangers of any hazard, you have to know there’s a hazard in the first place! A hazard is any practice, behaviour, or physical condition that can cause:

- Injury

- Illness

- Damage to property

- Damage to environment

- Loss to process

Three Steps to Hazard Identification

Step 1: Process Identification

In order to identify hazards, you first have to take a close look at all of the processes at your place of work. Examples of processes include:

- cleaning

- maintenance

- office work

- painting

- welding

- lift truck operation

- production facilities

- packaging

- security

- shipping & receiving

Step 2: Task Identification

The second step is to list every task performed for each process. For example, here are some of the tasks that are typically carried out by maintenance personnel:

- electrical installations and repair

- mechanical repairs and preventative maintenance

- groundskeeping & snow removal

- building maintenance

- H.V.A.C. upkeep

Step 3: Recognize Hazards within the Task

The third step is to recognize the hazards of each task. We call this “P.E.M.E.P.” because every hazard will fall into one of these five categories:

- People

- Equipment

- Materials

- Environment

- Process

People hazards could include:

- horseplay

- untrained employees

- lack of attention

- making poor decisions

- using improper techniques

- using inappropriate equipment

- rushing to get the job done

Equipment hazards could include:

- using improper equipment for the job

- using an improper technique

- points of operation causing nips, cuts, amputations

- exposure to moving parts

- poor maintenance leading to equipment failure

- failure of hand tools

- inappropriate personal protective equipment for the job

Material hazards could include:

- sharp, heavy or hot objects

- hazardous materials

- improper stacking or storage of material

- unsecured loads

- unknown load capacity

- lifted high into the air

- difficult to handle manually

Environment hazards could include:

- walking surfaces

- airborne contaminants

- congestion or clutter

- noise

- heat stress or cold

- vibration or radiation

- lighting

Process hazards could include:

- workplace design

- job design

- blind corners

- schedules for production

- ergonomic conditions

- improper equipment

- inadequate spill response measures

Assessing Hazards

Once you have identified the hazards that are present, you will need a method to prioritize RACE to the most serious risks first. In the case of airborne hazards, an assessment may be done through air sampling or constant monitoring. Testing can be initiated by your JHSC because of a request made by an employee. This initial testing should benchmark current conditions. That way, once you implement your control you can determine its effectiveness.

As an employer, it is your responsibility to ensure all hazards are monitored. If your organization is large enough to have a JHSC, you should make sure that they are informed about any monitoring or outcomes.

A designated worker-member of your JHSC or an employee representative is entitled to be present at the beginning of testing to help monitor test procedures and results.

When assessing a hazard we must know the accepted norms in order to judge the situation. For instance, when we take a sample of air we need to know what we are looking for, the level of acceptable exposure for employees without personal protection, and when we need to consider hazard elimination, substitution, or isolation techniques. In Ontario, we would look to Regulation 833: Control of Exposure to Biological or Chemical Agents (a regulation made under the Act) to provide guidance. The Ontario Ministry of Labour, Training, and Skills Development generally accepts the threshold limits published by the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH)—a non-profit organization based in the United States. These values list acceptable exposure levels to which an average worker can be exposed to without any adverse health effects.

When assessing hazards the following resources have a wealth of information on laws, standards, guidelines, and codes:

- Occupational Health and Safety Act (OHSA)

- Fire and Building Codes

- Ministry of Labour Standards & Guidelines

- CSA Standards

- Workplace policies and procedures

- Manufacturer and supplier instructions

Hazards can be assigned a priority classification to help you with scheduling and implementing the hazard controls recommended by the committee. There are many classification methods. It is up to the committee to adopt the most logical solution. The following is just one method:

- Class ‘A’ Hazard – A major condition or practice that is likely to cause serious, permanent disability, loss of a body part, death, or an extensive loss of building assets, equipment, or materials

- Class ‘B’ Hazard – A serious condition or practice that is likely to cause a serious injury resulting in the temporary disability of an employee or major damage to the building, equipment, or materials

- Class ‘C’ Hazard – A minor condition or practice likely to cause a non-disruptive, non-disabling injury or illness or non-disruptive property damage

Controlling Hazards

Once you have identified and assessed all hazards, the next step is to determine the effectiveness of existing controls and identify necessary improvements. Controls may be applied in a number of ways and in three different locations:

1. At the Source: The best way to control a hazard is to apply the control at the source of the hazard. Keep in mind that the best solution is always to remove the hazard from the workplace. However, you may discover that is not possible.

2. Along the Path: Controls along the path do not remove the hazard. Rather, they provide methods to alert employees that a hazard exists. The goal is to minimize employee exposure.

3. At the Employee: Controls at the employee include personal protective equipment (PPE), safety training, administrative procedures, and disciplinary actions. Controls at the employee level are subject to human error and should be considered the last alternative in control hazards. This is especially true in the case of P.P.E. Simply put, sometimes employees don’t wear their P.P.E. correctly or at all so this can be difficult to monitor and evaluate.

A variety of hazard controls may exist in the workplace. Often, a customized approach is required. There are three basic classifications of hazard controls:

- Engineering controls

- Administrative controls

- Personal protective equipment

Engineering controls could include:

- elimination

- isolation

- substitution

- automation

- machine guarding & re-design

Administrative controls could include:

- standard operating procedures

- training & education

- inspections & investigations

- work practice

- job rotation

- progressive discipline

- competent supervision

Personal protective equipment could include:

- hard hat & work boots

- gloves, sleeve protectors, aprons, & coveralls

- respirators or surgical masks

- hearing protection

- safety glasses, chemical goggles, & splash shields

- insulated or breathable workwear

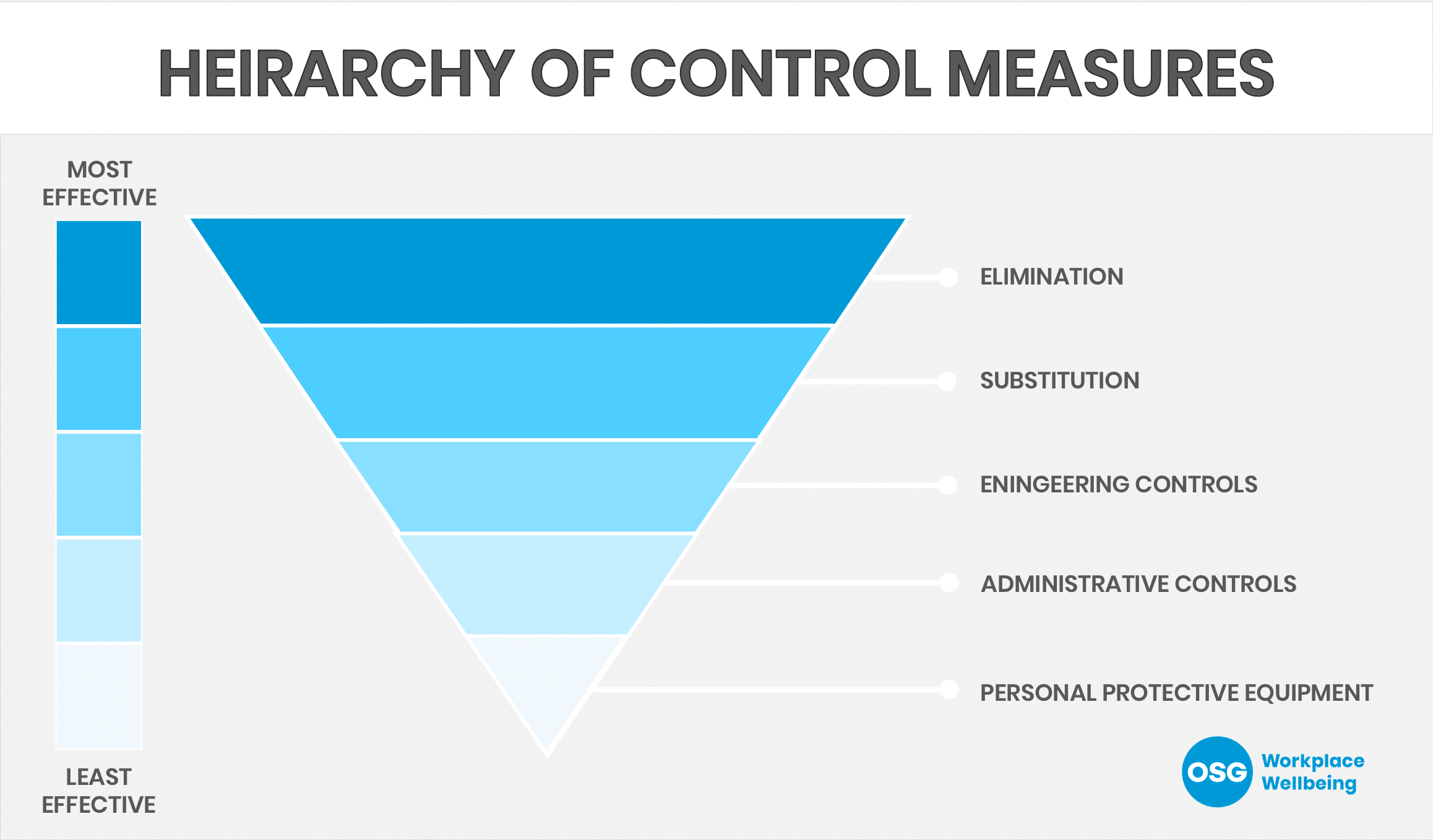

Priority should be given to hazard controls at the source using engineering controls. The last type of control to consider is PPE. This prioritization is called the “Hierarchy of Controls.”

The best-case scenario would include the implementation of multiple controls with a variety of backup controls in place should one control fail. An example of multiple controls for an environment such as a hazardous storage room may include:

- fixed gas monitors that continuously sample air. An alarm goes off when dangerous conditions are reached

- a monitoring station located outside of the chemical storage room that receives data from fixed monitors located inside of the storage room

- fire extinguishing systems within the chemical storage room that have controls located on the outside

- air exchange systems with scrub filters that recycle or clean ambient air

- cameras located within the storage room that are monitored by security

- windows leading into the room for visual assessments prior to entry

- locking doors to permit unauthorized entry

- signage that indicates a restricted area

- hazardous chemical training for all workers authorized to enter the storage room

- emergency response teams on standby when a worker enters the room

- self-contained breathing apparatus available to rescue workers

- policy and safe work procedures for assessing and controlling additional hazards

- personal air monitors to be worn by all workers entering the storage area

- schematic drawing provided and reviewed by members of the local fire department so they know what is being stored and its location; and

- chemical inventory process to document, update and track chemical inventories within the room

Evaluating Hazards

Once you’ve implemented your organization’s hazard controls they must be evaluated to determine their effectiveness. It’s important that hazard controls do not inadvertently introduce a new hazard while taking steps to eliminate, reduce, or control another. An example of this would be the introduction of anti-fatigue or ergonomic floor mats located at work stations throughout the plant. However, these mats could introduce a slip and trip hazard that must be considered prior to implementation.

An evaluation of the effectiveness of controls can be made by:

- interviewing workers affected by the control

- monitoring air quality, production values, and quality control

- observations of safe work procedures

- reviewing accident and incident reports

- comparing equipment diagnostics (before and after control measures have been implemented)

And remember, you will need to compare before and after control measures have been implemented. Committee members need to determine how to evaluate a hazard control before it is implemented. It’s a good idea for a hazard control to be measurable to determine if the hazard control is meeting or exceeding the goals. Committee members need to consider:

- How will the control be implemented?

- What is the schedule for implementation? Is it based on the hazard classification in an attempt to control the most serious hazards first?

- What is the feedback mechanism for evaluation?

- What is an acceptable result?

- Have we considered an alternative control if this one doesn’t work?

Regular workplace inspections are an important part of hazard identification. Using a checklist during inspections will help make sure you don’t miss any area of your workplace.

Download our free sample checklist to help evaluate different areas of workplace’s health and safety.

OSG Can Help

Does your organization need help identifying risks? Learn how a Gap Audit performed by one of our Health & Safety experts can help you identify risks and mitigate risks in your workplace.